The Pakistani drama industry is renowned for manufacturing magical pairings, couples whose on-screen chemistry pulls in viewers in the millions, often even billions. These pairings are often so aesthetically pleasing that the audience is willing to forgive almost everything else: weak writing, recycled into far more problematic tropes, questionable moral frameworks, and crippled character development.

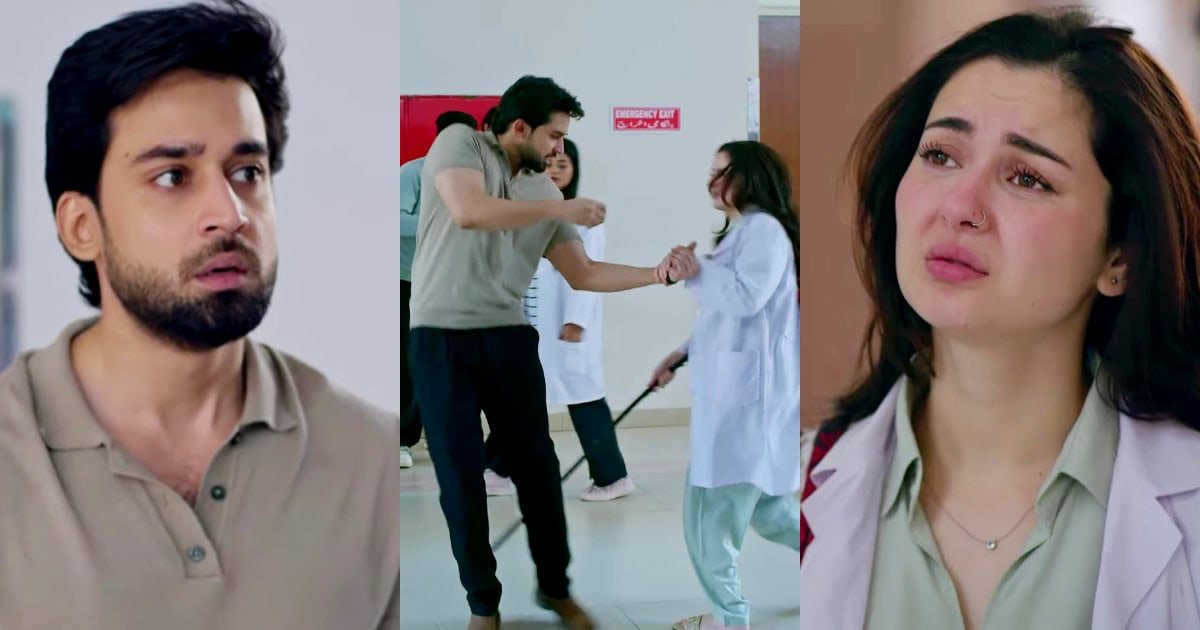

Currently, Meri Zindagi Hai Tu has taken over the internet, and the reason is obvious. Starring Bilal Abbas Khan opposite the ethereal Hania Aamir, the drama is written by Radain Shah and directed by Mussadiq Malik. Being aggressively marketed as a love story with nothing to offer as to what exactly that love is? Now that we are past the climax of the plot, it feels necessary to pause the chart-breaking OST by Asim Azhar and sketch out some key takeaways, along with the disturbing thoughts that kept creeping in while watching the show.

What Exactly Made This Script Stand Out to the Producers?

With the hype surrounding Meri Zindagi Hai Tu, one is automatically compelled to assume one of two things: either the drama is exceptionally well-written, or there is something off about it that we are being asked to overlook. The script, however, follows a painfully familiar equation. A rich, spoiled, emotionally volatile, and morally grey man meets an innocent, pious, career-driven woman, and what follows is sold to us as love.

Kamyar, the male lead, is introduced as a despicable playboy and a privileged brute. He beats up the heroine’s brother, torches her car, and treats accountability like a personal insult. Yet, predictably, his “transformation” begins the moment Ayra slaps him. Ayra’s slap doesn’t spark instant love; it bruises the ego of a man who has never been denied attention before.

What follows is not romance, but a series of stalking attempts and peak harasser behavior, cleverly softened by background scores and longing close-ups. Kamyar persistently inserts himself into Ayra’s life, eventually convincing the career-driven MBBS final-year student that he loves her and would “do anything” for her, except, of course, respect her autonomy.

The most disturbing part is how casually violence is embedded into this so-called love story. Kamyar sets Ayra’s car on fire, a car her father bought through hard-earned money as a graduation gift, while her father suffers a cardiac arrest inside the house. This act is a turning point, Kamyar’s best depiction of male-aggression. One argument leads to destruction, trauma, and terror, yet somehow, this becomes the foundation upon which romance is built. And in the most tone-deaf way, Ayra herself mindlessly succumbs to his love-wrapped harassment, even going so far as to ask him to marry her, declaring that she would “tolerate any hell” just to live with him. The drama frames this as devotion, but in reality, it exposes a disturbing narrative: abuse is forgivable, and women are celebrated for surrendering to it.

Can We Stop Selling Aggression as Romance, please?

What Meri Zindagi Hai Tu does particularly well, and by “well,” I mean dangerously, is romanticize obsession by packaging it in the charming face of Bilal Abbas Khan. Kamyar’s actions are repeatedly excused because he is attractive, persistent, and what is less talked about, but RICH and eventually “remorseful.” Now, from what I know, this is anything but love. Because I was reminded of when someone posted on X about how 50 Shades of Grey was only romantic because the guy was rich, otherwise it would’ve been an episode of “Sar-e-Aam”. Pretty sharp in contrast, but absolutely spot on.

The drama sells the idea that harassment becomes acceptable once the man falls in love, that stalking is merely passion misdirected, and that destruction is forgivable if the perpetrator looks good while doing it. The audience is encouraged to swoon, not question. To sympathize, not interrogate.

In real life, a Pakistani woman slapping a man like Kamyar would not be met with poetic redemption arcs. We have real examples, Sana Yousaf, the TikToker who paid the price for saying no; Khadija Shah, who was stabbed repeatedly by a class fellow for rejecting him. These are not fictional exaggerations. They are reminders of how dangerous it is to romanticize the boundary between love and violence in a society already hostile to women’s autonomy.

Ill-written, Incompetent, and Inconsistent Parents:

Equally troubling is the way Ayra’s parents are written, if one can even call it writing.

They are emotionally reactive, morally inconsistent, and entirely disconnected from their daughter’s reality. Initially, they reject Kamyar for his Playboy lifestyle, a decision that seems rational. But when Kamyar claims to have changed, they fail to teach Ayra the most basic emotional skill she will need in marriage: how to communicate, how to trust, and how to seek clarity before passing judgment.

When a defamatory video surfaces, later revealed to be a paid act orchestrated to tarnish Kamyar’s reputation, Ayra is shown as remorseful for not giving him a chance to explain himself. The point here is that if Ayra’s trust in Kamyar’s transformation was strong enough for marriage, her thoughtless decision to call it off without a conversation exposes not her morality, but the drama’s insistence on writing women as irrational. And her parents support her irrationality, in fact, implicitly blame her for making the wrong decision because, despite being marriage participants, they back off when things go wrong and shift the blame to her.

What follows is perhaps the most baffling parental behavior in the entire drama. Despite knowing that another man had stalked their daughter and attempted to physically attack her when she rejected his proposal, Ayra’s parents pressured her into marrying him. Then again, her father finds out about the guy’s involvement in plotting against Kamyar, and he calls off the wedding within 30 seconds. Later, her father supports her decision to apologize to

Kamyar for calling off the wedding, but when she decides to remarry Kamyar later, he threatens to sever all ties with her. Interestingly, there is no valid explanation available to understand what Ayra’s father exactly wants. The audience is only being served a medium boiled father figure with no sense of right or wrong, let alone a decision-making ability. Thankfully, it only helps in justifying why Ayra is always pathetically confused.

Women With Lives Only for Men:

On the other hand, the women in Meri Zindagi Hai Tu, including Ayra, exist almost entirely in relation to Kamyar. Ayra’s life revolves around him. Kamyar’s vengeful ex-best friend plots to defame him because she cannot process rejection. The woman featured in the viral video attempts suicide after being publicly shamed, yet even her trauma circles back to Kamyar, as she admits the entire act was an attempt to gain his attention.

No woman is allowed an independent emotional arc. No one has ambitions, desires, or moral agency that do not orbit Kamyar’s presence. Their pain, shame, and even survival are framed as footnotes to his story. Which raises a simple but crucial question: what exactly makes Kamyar so unforgettable?

Is it the obsessive stalking? The inability to differentiate between love and control? The readiness to destroy property and intimidate? Or is it simply that he is played by an actor charming enough for the audience to suspend its moral judgment?

Why Is This Still So Lovable?

What makes Meri Zindagi Hai Tu so widely consumed is not novelty, but familiarity. Women raised in deeply patriarchal homes are taught not to think because their intellectual potential is presumed to never match that of a man who flirts shamelessly, drinks without hesitation, and moves through life with unchecked entitlement. A man who casually dehumanizes the women in his own circle, dismissing them as characterless and unworthy, while their lives are written to revolve solely around him.

Against this backdrop, the pious, career-driven woman, untouched by love, untouched by desire, is elevated as morally supreme. Her purity becomes the justification for why the same man suddenly finds himself deserving of marriage. This narrative is repeatedly consumed, romanticized, and defended.

The only question left is whether we are ready to confront the consequences of loving it so much?

Article By: Maryam Shakeel

Maryam Shakeel is a writer known for her incisive observations. Engaged with global pop culture, she examines music, media, and celebrity narratives as social texts, tracing their political subtexts, cultural tensions, and the formation of public mythologies.

Our Commonly Asked Questions?

Unlike typical dramas, Meri Zindagi Hai Tu focuses on layered storytelling and character-driven emotions rather than relying solely on melodrama.

The drama highlights emotional dependency, family pressure, and societal expectations that influence personal choices in Pakistani households.

The drama revolves around complex relationships, emotional struggles, and personal sacrifices, exploring how love and circumstances shape life-changing decisions.

It emphasizes the importance of emotional awareness, mutual respect, and the consequences of unresolved trauma in relationships.